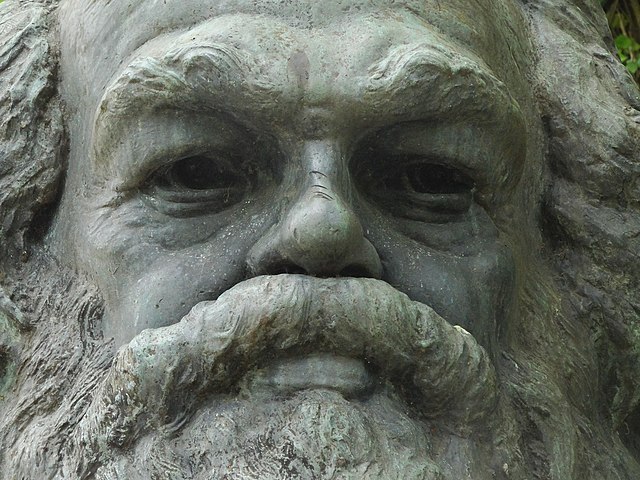

Karl Marx evokes strong reactions from both sides of the political spectrum. His work has inspired thousands of people to mobilise against class oppression, yet he remains taboo in several parts of the world. Economics is no exception.

Interestingly, while economists often dismiss Marx’s work (Meadowcroft 2008), he is simultaneously used as a strawman by professors to ensure that his critique never receives sincere engagement.1 As evident from the dearth of heterodoxy in most economics departments globally — as of 2016, less than 120 economics departments were offering Postgraduate or Undergraduate programmes globally (Jakob Kapeller and Florian Springholz 2016), Marxist perspectives in economics remain at the fringe.

Why is he such a polarising figure? The reasons range right from militarised propaganda against communism during the Cold War (Herman and Chomsky 2002) to fear of totalitarian regimes after the fall of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republic (USSR) or the rise of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) (Importance of European Remembrance 2019). However, the scope of this article will be limited to a simpler reason: misinterpretation, primarily by economists.

Marx and Communism

Contrary to popular opinion, he was not a messiah for the economy, nor did he prophesise the sequential destruction of capitalism. For Marx and his frequent collaborator and close aide, Friedrich Engels, Communism was the process of dismantling capitalism. “Communism is for us not a state of affairs which is to be established, an ideal to which reality [will] have to adjust itself. We call Communism the real movement which abolishes the present state of things. The conditions of this movement result from the premises now in existence.” (Marx and Engels 1976, 42)

It is crucial to understand this definition because several dismissals of Marx are premised upon the incorrect categorisation of the state of affairs in the erstwhile USSR and PRC as communism.

However anticlimactic, Marx’s work merely critiques capitalism, and the value of his work lies in his sharp analysis of the social relations within capitalism and how they inform the interactions and transactions of the people embedded in capitalism. His study also thoroughly examines the claims made by proponents of the free market. By illustrating capitalism’s internal contradictions, he builds a case for why it will eventually have to fall apart.

At a certain stage of development, the material productive forces of society come into conflict with the existing relations of production or […] with the property relations within the framework of which they have operated hitherto. From forms of development of the productive forces these relations turn into their fetters. Then begins an era of social revolution. The changes in the economic foundation lead sooner or later to the transformation of the whole immense superstructure. (Marx 1999, 2)

Marx vs Economics

Thomas Sowell criticised Capital as a “detour into a blind alley” (1958, 220), an opinion shared by many economists like John Maynard Keynes, who famously referred to Capital as “obsolete” (1991, 300). However, a close examination of their remarks reveals a poor comprehension of the object, methods and the purpose of Marx’s analysis — which was focused on a theoretical abstraction of the way capitalism produces social and economic relations within itself and the impact of these relations.

The Labour Theory of Value (LTV), laid down by classical political economists, is incorrectly attributed to Marx by several of his critics. It also supports a large chunk of the alleged irrelevance of his theories. The LTV suggests that the value of commodities is determined by the labour-time necessary for production (Prychitko 2007). However, Marx’s utilisation of the LTV merely critiqued the approach of bourgeois economics.

Neither attempting to prove or disprove the LTV, Marx was concerned with the why and how the value of commodities was being determined in the first place: “Political Economy has indeed analysed, however incompletely, value and its magnitude, and has discovered what lies beneath these forms. But it has never once asked the question why labour is represented by the value of its product and labour-time by the magnitude of that value.” (1887, 52). If this mode of analysis were to be utilised to understand neoclassical economics, one would question where it derives its assumptions2 from and why these assumptions are taken for granted.

By situating his critique in a present state of capitalism, Marx illustrates how capitalism contributes to producing, reproducing and, in a certain sense, trapping individuals in systems of social relations. Bourgeois economics mystifies these relations so that individuals don’t even realise their embeddedness (166-67).

In fact, as economists, we are trained right from the undergraduate level to solve economic problems, without questioning their very premise — whether they can even be done away with. Marx’s analysis reveals that the financial crises in our economies are not outliers but an essential part of its survival (Heinrich 2012, 96).

For example, what Marx calls surplus labour time is the extra time in which a worker produces value for the capitalist they are working for. The value generated during this time frame belongs to the capitalist, referred to as surplus. This surplus is necessary for capitalists to invest in raw materials, machinery, and other capital-generating instruments to keep their businesses running. Hence exploitation used as a moral judgement against capitalists, according to Marx, is the appropriation of surplus value inherent to capitalism (Heinrich 2012, 167-78). To survive, it is in the best interests of capitalists to maximise this surplus value, which in real life translates to “disproportionate”3 wages for very long hours of toil and abysmal working conditions.

Employing Marxist Critiques

So what was Marx’s contribution to economics as a social science? While Marx never referred to himself as an economist, his tools of analysis, systemic approach to the political economy and acute observations of capitalism hold great potential to enrich economic research and practice. First and foremost, they push us to reflect on whether we are asking the right questions, which is an essential aspect of public policy.

The Platform Economy Discourse

For instance, delivery services, especially during the COVID-19 lockdowns, cemented their place in the global political economy as essential services (Athreya 2020). In the fight for the rights of platform workers to gain recognition as employees, several opponents cite flexibility against their recognition, prompting the question: how do we preserve the flexibility platforms claim to provide their workers while ensuring their legal rights?

But if one closely examines this claim of flexibility, as several scholars from Marxist traditions have, it becomes plain that it is nothing more than red herring. Platforms and big data lend capitalistic processes unprecedented computational power and opaqueness, depriving workers of fundamental human rights and subjecting them to abject working conditions, low pay and isolation (van Doorn 2019). While they are “free” to choose which work they take up, algorithms reduce this choice to an illusion (Tomassetti 2020). Simply put, the claim of flexibility is just a myth (Athreya 2022).

Hence, in the formulation of policy for platform labour regulations, it is necessary to go beyond the obscure economic analysis of platform delivery services. When one employs a Marxist critique, it becomes apparent that the socioeconomic relations in which individuals and consumers are embedded in these systems play a profound role in setting the stage for these transactions. Not only must we question legal rights and issues of labour expropriation, but also the nature of the platform under capitalism itself (Morozov 2019).

What makes it difficult to question capitalism in such discourses has much to do with the omnipresent perception of it — capitalism has always been and will continue to exist. However, capitalism emerged as a social order as recently as the 16th century (Boettke and Heilbroner 2022). Although exchange, trade and other economic activities were always a part of human interactions, Marx notes the particular manner in which relations emerged under capitalism was new (Heinrich 2012, 14-18). Moreover, through this, he leads us to perhaps the most crucial path of inquiry, the one envisioning a post-capitalist society.

Why Read Marx?

“It is easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism…” cultural critic Mark Fisher (2009) correctly notes. The idea of developing a classless, stateless society hence becomes an impossible task. However, as economists, we ought to take up this challenge that requires us to think far beyond policies and legislation changes.

Much of our work as economists fixates on reforming a system that keeps breaking in newer ways. We must go beyond trying to fix our economies. Hence with a foundation in Marxist critiques of the political economy, we can not only demystify the untameable beast but also dare to imagine a future without it. It is easier said than done, especially within the ambit of current economic institutions.

As economists who play essential roles as policymakers, development professionals, and researchers, Marxist critiques of the political economy provide us with tools to expand the scope of the ambit of economics as a discipline and further rethink some assumptions we take for granted. Marxist perspectives in economics allow us to view the economy as a part of the greater society and how it worsens other social oppressive mechanisms such as caste, race and gender.

A common refrain supporting capitalism is that it breeds innovation by incentivising people to be creative. What better way to innovate than to transcend capitalism entirely, a task that heavily relies on faith in human ingenuity?

References

Athreya, Bama. 2020. ‘A Pandemic Is No Time for Precarious Work’. Medium (blog). 27 March 2020.https://bamaathreya.medium.com/a-pandemic-is-no-time-for-precarious-work-28276df00821.

Athreya, Bama. 2022. ‘Bringing Precarity Home: Digitized Piece Work and the Fiction of Flexibility’. Medium (blog). 29 January 2022.https://bamaathreya.medium.com/bringing-precarity-home-digitized-piece-work-and-the-fiction-of-flexibility-6a312ced743a.

Boettke, Peter J., and Robert L. Heilbroner. 2022. ‘Capitalism’. In Encyclopedia Britannica.https://www.britannica.com/topic/capitalism.

D’Alisa, Giacomo, Federico Demaria, and Giorgos Kallis, eds. 2015. ‘Introduction: Degrowth’. In Degrowth: A Vocabulary for a New Era, 6. New York ; London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

Doorn, Niels van. 2019. ‘On the Conditions of Possibility for Worker Organizing in Platform-Based Gig Economies’. Notes From Below, 8 June 2019.https://notesfrombelow.org/article/conditions-possibility-worker-organizing-platform.

Fisher, Mark. 2009. ‘It Is Easier to Imagine the End of the World than the End of Capitalism.’ In Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative?, 1. Zero Books. Winchester, UK Washington, USA: Zero Books.

Friedrich Engels, ed. 1887. Capital: The Critique of Political Economy. 1st ed. Vol. 1. Progress Publishers, Moscow, USSR.

Heinrich, Michael. 2012. An Introduction to the Three Volumes of Karl Marx’s Capital. New York: Monthly Review Press.

Herman, Edward S., and Noam Chomsky. 2002. ‘A Propaganda Model’. In Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media, 29–31. New York, NY: Pantheon Books.

Kambites, Carol Jill. 2014. ‘“Sustainable Development”: The “Unsustainable” Development of a Concept in Political Discourse: The “Unsustainable” Development of a Concept’. Sustainable Development 22 (5): 336–48.https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.1552.

Kapeller, Jakob, and Florian Springholz. 2016. ‘Heterodox Study Programs’. In Heterodox Economics Directory, 6th ed., 61–128.http://www.heterodoxnews.com/hed/study-programs.html.

Keynes, John Maynard. 1963. ‘A Short View of Russia’. In Essays in Persuasion, 300. Norton Paperback. New York: Norton.

Marx, Karl. 1999. ‘Preface’. In A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy, 2.https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/download/Marx_Contribution_to_the_Critique_of_Political_Economy.pdf.

Marx, Karl, and Friedrich Engels. 1976. ‘The German Ideology’. In Karl Marx, Frederick Engels. Volume 5, Marx and Engels: 1845-47, 42–43. London [England]: Lawrence & Wishart.

McPeek, Melinda. n.d. ‘Red Scare · Decoding Political Propaganda’. Nabb Research Center. Accessed 30 September 2022.https://libapps.salisbury.edu/nabb-online/exhibits/show/propaganda/fear/red-scare.

Meadowcroft, John. 2008. ‘Credit Crunch Brings Marx Back into Fashion’. The Times, 23 October 2008.https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/credit-crunch-brings-marx-back-into-fashion-ln9g5qhmmp7.

Morozov, Evgeny. 2019. ‘Capitalism’s New Clothes’. The Baffler, 4 February 2019.https://thebaffler.com/latest/capitalisms-new-clothes-morozov.

Pollin, Robert. 2018. ‘De-Growth vs a Green New Deal’. New Left Review, no. 112: 6.

Prychitko, David. 2007. ‘Marxism’. In The Concise Encyclopedia of Economics, 2nd ed. Library of Economics and Liberty.https://www.econlib.org/library/Enc1/NeoclassicalEconomics.html.

Shiller, Robert J. 2013. ‘Why Innovation Is Still Capitalism’s Star’. The New York Times, 17 August 2013, sec. Business.https://www.nytimes.com/2013/08/18/business/why-innovation-is-still-capitalisms-star.html.

Sowell, Thomas. 1985. ‘The Legacy of Marx’. In Marxism: Philosophy and Economics, 220. New York: Morrow.

‘The Importance of European Remembrance for the Future of Europe’. 2019. In Joint Motion For A Resolution. European Parliament.https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/RC-9-2019-0097_EN.html.

Tomassetti, Julia. 2020. ‘Algorithmic Management, Employment, and the Self in Gig Work’. In Beyond the Algorithm: Qualitative Insights for Gig Work Regulation, edited by Deepa Das Acevedo, 123–45. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108767910.008.

United Nations Development Programme. n.d. ‘About’. Sustainable Finance Hub. Accessed 29 September 2022.https://sdgfinance.undp.org/about.

Weintraub, E. Roy. 2007. ‘Neoclassical Economics’. In The Concise Encyclopedia of Economics, 2nd ed. Library of Economics and Liberty.https://www.econlib.org/library/Enc1/NeoclassicalEconomics.html.

Based on author’s discussions with students in various economics departments in India ↩︎

- People have reasonable preferences for possible outcomes. 2. People optimise their utility, and businesses maximise their profits. 3. Individuals make independent decisions based on complete and pertinent information. (Weintraub 2007)

Calculating whether wages are proportionate or not further relies on abstract assumptions. How does one justify compensation of Rs. 10 per hour for a miner versus Rs. 1000 per hour for a therapist? ↩︎